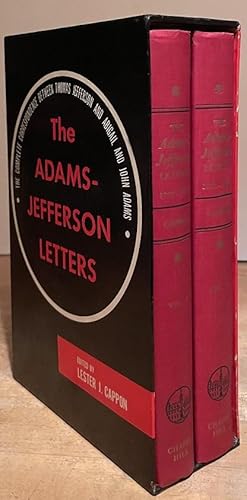

It was undoubtedly difficult for Abigail to write to Jefferson, then president of the U.S. During their short time together Abigail and Polly grew close. Arriving in England, Jefferson had arranged for Abigail to pick up and care for Polly until she could be reunited with him. Very reluctant to leave the familiar for the foreign, Polly actually had to be tricked to board the boat that would transport her to Europe.

Back when the Adamses had been stationed in England and Jefferson in France (John was the American minister to Great Britain and Jefferson minister to France), Jefferson had sent to Virginia for his daughter who had been living with relatives. Unbeknownst to her husband, Abigail Adams initiated a correspondence with Jefferson in 1804 after the death of the Virginian’s youngest daughter Mary, often called Polly. There was, however, a brief correspondence that passed between those locations in those silent years involving Thomas Jefferson and an Adams – Abigail, wife of the second president. But a decade would pass in which the men did not meet nor correspond with each other. Only after both men were retired to their beloved homes, Adams at Peacefield in Quincy, MA, and Jefferson at Monticello in Charlottesville, VA, would the friendship be renewed.

But the strain of political discord and partisan strife would first stretch and finally break the bonds first forged in Philadelphia. Partners in declaring independence, the pair would become like brothers while on assignment in Europe. Arguably the most fascinating friendship in early America was between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)